The Structural Roots of Greater Boston's Housing Crisis

How neighborhood defenders and discretionary zoning have suppressed new housing for decades

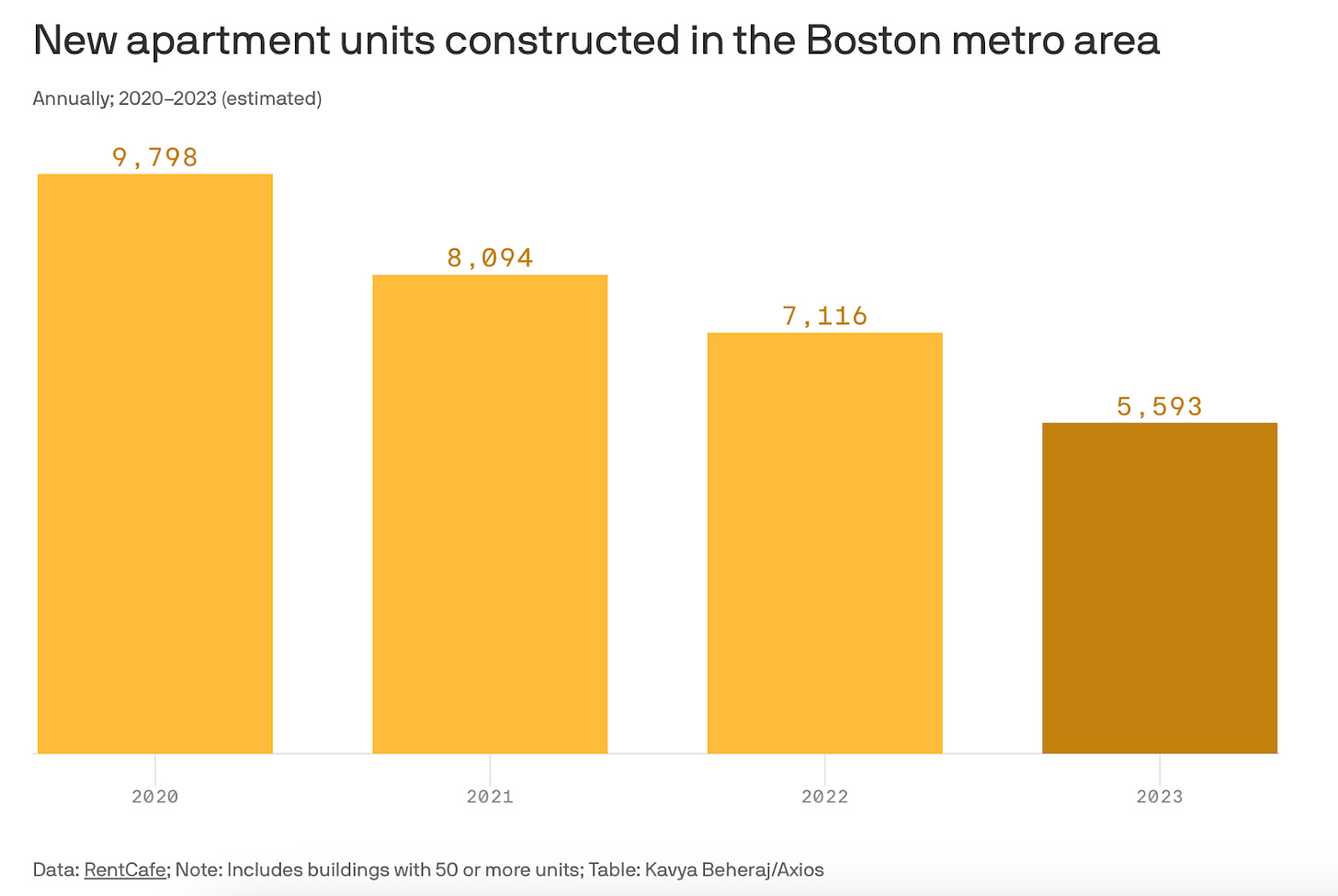

According to a recent analysis, the Boston metro area will build roughly half as many apartments in 2023 as it did in 2020.

The sharp decline in construction is worrying because the only way to sustainably address Boston’s housing crisis is to build more housing. The facts of the crisis are well known by now: the rent for a one-bedroom apartment in Massachusetts is up 6.5% YoY, the average one-bedroom apartment in Boston costs $2,750 per month, and 52% of Boston renters are cost-burdened.1 Boston’s vacancy rate has been under 1% for almost two years, far below the 6% vacancy rate that is commonly considered healthy. With such a tight rental market, renters have a hard time finding a new apartment, and landlords have the leverage to continue increasing rents. The best way to deal with this crisis would be to build a lot more apartments to meet the high demand, but Boston isn’t doing that.

The proximate causes of the decline in apartment construction are likely the macroeconomic effects of COVID: elevated interest rates, high material costs, and a lack of skilled workers. Boston Mayor Michelle Wu’s recent rent control proposal, although unlikely to take effect, may also be spooking developers, who are already being squeezed by narrow profit margins.

However, the lack of new housing in the Boston area is not a recent, post-COVID phenomenon. Rather, there are structural conditions that have suppressed housing production for decades. In this post, we’ll focus on two issues: (1) the unrepresentative influence of “neighborhood defenders” on new housing and (2) zoning codes that require most multifamily projects to go through a discretionary approval process. The combination of discretionary zoning with neighborhood groups’ effective veto over new housing means that developers are uncertain whether any given project will be approved, even if it fits zoning requirements. The tens of thousands of dollars that developers have to spend in the zoning approval process, as well as the months- or years-long delays in construction, go straight into higher rents. In the worst cases, housing developments are blocked all together.

Groma has run into these barriers firsthand, which prevented us from building over a dozen affordable, income-restricted apartments in Roxbury and Everett. To give a sense of what developers experience, we’ll describe how both of these projects were blocked. We’re not looking for sympathy by telling these two stories; rather, we want to show how the systemic predisposition against new housing operates in practice. By understanding how difficult it is to get even a single new multifamily project approved, it’s easy to see how local control of housing development has spiraled into a crisis.

We’re not arguing that there should be no community input on housing developments or that zoning should be abolished. Instead, we’re saying that the Boston area’s current system for approving new housing caters too much to objections from existing homeowners. Given the scale of the housing crisis, heavy weight must be placed on approving lots of new construction and density. Reforming the neighborhood input process and transitioning to clear, by-right zoning would go a long way towards boosting housing production and bringing down rents.

Neighborhood Input

Background

Massachusetts has a deeply rooted tradition of strong local control in its towns and cities. The majority of towns in the state still use a town meeting format, where any resident can attend and vote on budgetary issues and bylaws. In the Boston area, this culture manifests itself strongly in housing development, particularly at the neighborhood level.

After World War II, neighborhood mobilization became particularly pronounced in Boston. In the 1950s, Mayor John Hynes’s “urban renewal policy” led to the razing of entire neighborhoods (often poor ones with large immigrant populations), most notably the West End. West End residents formed the “Committee to Save the West End”, which protested city council meetings, passed out fliers, and sued to prevent the demolition of their homes. Ultimately, the campaign was unsuccessful, and Boston began to tear down the West End in 1958, displacing 12,000 residents, most of whom left the city because they couldn’t afford rent in other neighborhoods. Today, the West End is mostly non-residential, populated by Government Center, the Mass. General Hospital complex, and some residential high-rises. The destruction of the old West End can be seen as a cautionary tale of what happens with too little community input on development decisions. The cheap, dense housing that used to make up the West End was a vital source of market-rate, affordable housing.

In 1985, Mayor Ray Flynn’s citywide rezoning plans institutionalized the influence of neighborhood groups over Boston’s housing development. Flynn sought to push development away from downtown without alienating residents in surrounding neighborhoods. To do so, the Boston Redevelopment Authority, or BRA (now the BPDA), designed a citywide rezoning plan that was composed of smaller plans negotiated between the city government and neighborhood groups. Amendments made to the zoning code in 1993 reinforced the power of individuals and local community organizations to delay the rezoning plans. In the end, the rezoning process for each neighborhood took an average of four years.

The Flynn administration created a system in which neighborhood councils and planning/zoning advisory committees had formal and informal powers over the development of new housing. Early on, one researcher noted that certain neighborhood groups without formal power gained the ability to assert tremendous influence within the BRA, which framed its willingness to easily bend to local pressures as a sign of its responsiveness. It was in the 1980s that the current norm emerged: development projects will require the approval of neighborhood groups to move forward.

In Boston and many surrounding towns, most development projects require at least one public hearing by the local planning board. Officials have an informal (but powerful) commitment to heavily weigh community opinion in their approval of these projects, rather than the merit of the projects themselves or the city’s needs.

We want to be clear that planning boards should ask for and listen to community input on projects, as new development can create externalities (positive and negative) for the surrounding neighborhood. But the current system doesn’t properly distinguish between reasonable input and NIMBY objections that are intended to stop any new development.

Homeowners in a nearby suburb of Boston might see little upside to building new apartments due to increased traffic or the addition of more children to the public schools. After all, the negatives of new development (noise, construction, etc.) are localized, while many benefits are spread out across the larger city or region. However, residents might not recognize that there are local benefits that come with increased density. Dense housing allows towns to be more walkable and to sustain more varied amenities. It also has significant environmental benefits and supports greater agglomeration effects, which help the local economy.

It’s important to engage with opponents to new housing, hear their concerns, and try to have a genuine conversation with them. Regardless, outspoken local opponents, who often aren’t representative of their community, shouldn’t wield effective veto power when Greater Boston has a crushing need for more housing.

Neighborhood Defenders

To understand the warped nature of community input on housing development, it’s useful to bring in the concept of “neighborhood defenders” from the work of BU professors Katherine Einstein, David Glick, and Maxwell Palmer. Neighborhood defenders are people who try to block, or at least severely constrain, local housing development in the name of supposed neighborhood interests. They are usually self-appointed representatives of a community, either acting on their own or as part of a civic organization. (Civic organizations can appear to be representative of a neighborhood, even though they are often run by a small group of residents and are rarely elected by the whole community.) By exploiting bureaucratic channels and connections in local government, neighborhood defenders postpone development projects to drive developers away or force them to make significant concessions, usually by reducing the number of planned units.

Neighborhood defenders are generally unrepresentative of the communities they purport to represent. In their research, Einstein, Glick & Palmer found that neighborhood defenders tend to be older, well-off homeowners who have spent most of their life in a particular neighborhood. These are the people who have the time to attend planning board meetings that are often in-person, run for multiple hours, and take place during the workday or on weekday evenings. Residents who work, have to pick up children in the evening, rent, or are financially insecure are far less able to attend meetings. These people, who may be more likely to favor new housing to bring down rents, are underrepresented at community input meetings, which skews officials’ understanding of public opinion. For example, Einstein, Glick & Palmer analyzed the planning board minutes from 97 cities/towns in Massachusetts. They found that nearly 75% of public comments were from homeowners, but less than 50% of voters in those communities owned a home.

Neighborhood defenders’ NIMBYism may be driven by their interpretation of the costs and benefits of nearby development and/or a general skepticism of change. As mentioned earlier, neighbors are the main bearers of the negative externalities of construction, namely increased noise and traffic. Furthermore, given their deep roots in particular neighborhoods, defenders tend to feel more entitled to shape their neighborhoods’ development. It’s understandable that they may be reluctant to allow their community to change - it’s a human instinct to prefer the familiar. The problem is that this resistance to change actively perpetuates a crippling housing crisis. Poorer people and younger generations can’t find the accessible, affordable housing that prior generations had access to. Older homeowners who want to downsize and remain in their communities can’t sell because they can’t find anything to buy. We can find ways to address the short-term costs of construction and to incorporate suggestions from communities, but we fundamentally need to overcome the systems that prevent more housing from being built.

Opposition to Affordable Housing in Roxbury

In 2020, Groma purchased Property A, a vacant six-unit rental property in Roxbury. Our original intention was to demolish and replace it with 14-28 apartment units, 50% of which would have been affordable for tenants at 30% of the area median income (AMI). 30% of AMI is the most stringent affordability standard, defined as “extremely low” income by the federal government. Because of the below-market affordable units, this project would not have been very lucrative for Groma, but it would have greatly benefited Roxbury, one of the lowest-income neighborhoods in Boston. In the end, this didn’t matter, as we sold the property (unchanged) a year later. Profit margin was not what ultimately prevented the realization of this project.

Mainly due to opposition from neighborhood groups and local bureaucracy, Groma was blocked at each step of the redevelopment process. To start, the Boston Landmarks Commission, without citing a specific reason, indefinitely delayed demolition of the building.

Next, although Property A was on a street made up of mostly three-story homes, it was part of a high-density zoning area, and the new development would not have required zoning relief. The BPDA told us that we needed the blessing of a small civic group in Roxbury before the development could move forward, despite the project being in compliance with zoning rules,

Before we even spoke to the group, they expressed their opposition. The anti-development arguments provided by members ran the gamut. We were accused of “aggressively” moving into Roxbury, menacing the neighborhood with our efforts to build “cheap” apartments that would be too dense and modern to fit in with the neighborhood character. In other words, they claimed that Roxbury was not in need of, and indeed would be threatened by, dense, affordable housing. The neighborhood group refused to meet with anyone from Groma, effectively killing the project. After more than a year with no progress on getting approval, Groma decided to sell the property.

The story of Property A shows many of the flaws with the community input system. The BPDA never weighed the actual merits of Groma’s project or the needs of Roxbury and Boston, despite the project not requiring zoning relief. There was no consideration of the urgency of the housing crisis nor the benefits of adding a considerable number of affordable units.

In addition, the BPDA gave absolute veto power to a neighborhood group, rather than setting up a process to solicit genuine community feedback. It was unclear how representative the community group actually was of the views of Roxbury, and it appeared that the group made its decisions behind closed doors, outside the public view. We had no way to bring Groma’s case publicly to the Roxbury community because an unelected, vocal minority was selected to represent the interests of the neighborhood.

Given how the development process for a single multifamily development on Property A went, it’s easy to see how the current development system has systematically undersupplied new housing in a way that hasn’t kept up with Boston’s population or needs.

Discretionary Zoning

The other structural factor holding back the Boston area’s housing production is overly restrictive, discretionary zoning.

Before diving into the discretionary aspect, we want to briefly explain what we mean by restrictive zoning. Each town/city is responsible for its own zoning rules. In Greater Boston, 70% of municipalities have 80+% of their residential land zoned exclusively for single-family homes. It’s illegal to build any apartments or multifamily homes on the vast majority of land around Boston. As the regional economy has boomed over the last 40 years, developers haven’t been able to build enough new housing to meet the immense demand to live here, in large part because they’re often only able to build setback, single-family homes.

Many of these residential zoning restrictions aren’t based on the actual capacity of the land or infrastructure to bear housing. For example, more than half of the municipalities in Greater Boston have a minimum lot size of at least an acre for 50+% of their land area. An acre is 43,560 sq. ft., almost the size of a football field. The median new single family home in the US is 2,299 sq. ft., so over 15 new homes could comfortably fit on a single acre. These high minimum lot sizes artificially constrict the number of houses that can be built in any town, inflating the prices of suburban homes that are within commuting distance of Boston.

Restrictive zoning is used to keep less affluent residents out of wealthy suburbs and neighborhoods. However, these restrictions ultimately make it harder for towns to respond to the changing needs of their population. Retirees who want to downsize and stay in their communities have no smaller housing options, while young people, even highly-paid professionals, are pushed out due to unaffordable housing costs. Communities with restrictive zoning risk stagnation, as the aging population can’t find anyone to buy their massive homes, and new families can’t move in to sustain local businesses.

Discretionary Zoning as a Deterrent to Multifamily Housing

Besides being highly restrictive, multifamily zoning in Boston and surrounding communities is discretionary, which makes it even more difficult to build new housing. Discretionary zoning means that a project must go through a review process by a planning board before it can move forward. This process usually includes neighborhood input sessions, and it gives broad latitude to the members of the board to approve or reject a development. This approach is opposed to “by-right” zoning, which means that a project has to be approved so long as it meets set criteria laid out in the zoning code. The developer will generally have to submit a permit application and design plans, but these are a formality, as town officials don’t have the power to block a project in compliance with the zoning requirements.

Prior to the 1960s, most development in Greater Boston was zoned as-of-right. But beginning in the 1960s, towns made more of their zoning codes ad hoc. Today, municipalities surrounding Boston generally zone the lowest density uses of residential land (e.g., single-family homes) by right, while higher density uses (like multifamily homes and apartments) have discretionary zoning. In a 2019 report, researcher Amy Dain found that, from 2015-2017, just 14% of multifamily developments were permitted by right in Greater Boston. 57% of multifamily units had to go through a special permitting process, while the other 22% was built under Massachusetts’ Chapter 40B law. (40B allows developers to bypass many local zoning barriers to multifamily construction if the project sets aside 20-25% of its units for low-income residents.)

Under this system, developers are incentivized to build single-family homes because the discretionary approval process adds significant costs and uncertainty to multifamily projects. Developers have to spend tens (or hundreds) of thousands of dollars in legal and consultant fees to navigate the approval process, which often turns into a negotiation between the municipality and developer. The planning board may push for fewer units, require extensive changes to construction plans, and/or micromanage aspects of the proposal.2 Wielding the power of discretionary review, board members can force their personal preferences onto projects, separate from the content of the zoning code. Developers have to spend substantial amounts of money to address these requests and revise their plans. In addition, as detailed earlier, neighborhood defenders will often advocate against multifamily projects, placing significant pressure on board members to deny approval.

Multifamily developers also have to account for the indirect expense of their project being delayed. A recent study from Los Angeles found that “by-right projects were permitted 28% faster than discretionary projects, controlling for project and neighborhood characteristics”. The median approval of a by-right project with normal zoning was under 500 days, while the median approval for discretionary projects was 748 days. That difference in approval times is significant given how narrow the margins are in new construction. A project’s financing may fall through due to months-long delays, or the developer will have to eat the cost of unused materials and contractors waiting to begin work. The paper found that “by-right projects also had less variance in their approval times”. The standard deviation for approval of a by-right development with regular zoning was 211 days, while approval for discretionary projects had a standard deviation of 407 days. Given the massive uncertainty that discretionary projects face, developers are more reluctant to enter into those developments.

The LA example shows that, by forcing multifamily construction to go through the discretionary approval process, towns can effectively place a tax on multifamily projects through additional legal costs and time delays. This pushes developers to mostly build single-family homes due to their lighter regulatory burden. Towns are thus able to suppress the construction of new apartments and multifamily homes in Boston’s nearby suburbs.

Discretionary Zoning as Political Currency

Boston’s issues with discretionary zoning stem from its lengthy, out-of-date zoning code. At 3,791 pages long, Boston’s zoning code is 1,000 pages longer than New York City’s, despite New York having thirteen times the population.

Unlike other cities in the US, most residential construction in Boston requires a variance from zoning. Boston regularly reviews more than 1,000 zoning relief applications each year, while most other major cities receive fewer than 150 applications. This is largely because Boston’s zoning code, first adopted in 1924, has been revised through hundreds of piecemeal amendments. The code retains many antiquated clauses, and, due to the high number of ad hoc amendments, much of the zoning in the code doesn’t match the existing built environment. Many of Boston’s buildings and homes would be illegal to build under the current zoning rules. For example, 58% of parcels in the city are in violation of current floor-to-area ratio rules.3 Hundreds of thousands of parcels are considered “nonconforming” because zoning rules changed after buildings were already constructed on the land. Owners may continue to use their property in the nonconforming state, but they can’t make any changes because that would be considered making the nonconformity “worse”.

In order to improve or develop a nonconforming property, the owner has to apply for a zoning variance. Because so many properties in Boston are nonconforming, almost all new multifamily and apartment construction has to go through discretionary review by the Zoning Board of Appeal. In addition, in order to conduct a demolition, developers have to get approval from the Boston Landmarks Commission, even if the building isn’t a protected landmark.

Similar to the suburbs, this extensive discretionary zoning process adds enormous costs in legal fees and delays, as well as uncertainty, to new housing construction. It’s even worse in Boston because there are few areas where the by-right zoning matches the current use of the land.

Especially in Boston, discretionary zoning, and therefore most construction, is highly influenced by political and personal connections. With the power to approve variance petitions, the Zoning Board of Appeal can effectively rewrite any aspect of the zoning code for individual projects. It’s hard for developers to know whether a variance will be approved solely by looking at the zoning laws; rather, they need the right connections with neighborhood civic groups, politicians, and planning board members. Two homeowners with identical houses who want to make the same renovations could go through completely different review processes. One might get their variance in a day, while the other might spend $15,000 in legal fees over months to be approved.

The city’s control over zoning variances serves as a form of political currency. Sophisticated and wealthy players can leverage their connections with public officials to get their projects approved, placing regular people and outsiders at a disadvantage.

Some city officials have argued that the discretionary, project-by-project nature of construction in Boston is good because it gives the city leverage over developers. Under this system, neighborhoods have the ability to extract concessions out of builders to fund public projects and to ensure that they are giving back to the community. However, in practice, a small few well-connected residents negotiate narrow benefits that benefit themselves, and neighborhood defenders gain leverage to force developers to lower the number of units built.

In addition, the current discretionary system turns new construction into an adversarial process that suppresses new construction. Developers should have clear, by-right standards for what can be built, with room for community input. Instead, developers have little idea what concessions community groups or planning boards will require. This adds more uncertainty and costs to projects, stopping some developments and driving up the rents in the housing that is built. New construction can become a proxy fight between political actors in Boston, with desperately-needed new housing caught in the middle.

Undue Influence on Discretionary Zoning in Everett

In 2020, Groma acquired Property B, a run-down rental property with three units in Everett, MA. A construction survey suggested that the entire parcel could physically hold 16 new apartments, but the lot was only zoned for three units. The property was in need of renovation, and Groma wanted to add an additional unit as part of the project, but that would’ve required a zoning variance. It was indicated to us that the planning board would not support an extra unit, so we moved forward with renovating the three units in the house.

However, we soon learned that the abutter to Property B was the relative of a former public official in Everett. The neighborhood was old, with families who had been there for generations and didn’t want to deal with new development. The planning board continually delayed our permit to begin work on Property B, and we learned that the abutter had used his personal connections to scuttle our application.

After more than a year without approval, Groma decided to sell the property. Groma agreed to terms with a buyer who wanted to turn the property into townhouses. However, the buyer became evasive before signing the purchase and sale agreement. It turned out that the abutter had been in contact with the buyer. The abutter negotiated the purchase of one of the future townhouses from the buyer at-cost, presumably in exchange for supporting the project through the zoning approval process. Eventually, Groma closed on the deal, and we sold Property B to the buyer.

Again, we’re not looking for pity here, as Groma made out fine by selling the property. However, this story shows how vulnerable Greater Boston’s discretionary zoning is to personal influence. The abutter to Property B was able to extract a townhouse at-cost, simply due to his connections with the planning board. This kind of undue power over development shows why it’s so hard to build in Greater Boston, which is a big reason why the region has struggled to increase our housing supply to meet the current crisis.

Solutions

In this essay, we’ve shown how the warped nature of neighborhood input and discretionary zoning systematically suppresses new housing development, exacerbating the Boston area’s housing crisis. Fixing these issues won’t be easy. Reforms will need to happen at the local level, within individual towns and cities, and at the state level, by pressuring Massachusetts officials to reduce the amount of local control over housing production. Laws like the recently passed MBTA Communities Act and the YIMBY Act, which is still in committee on Beacon Hill, are steps in the right direction. In addition, we support the following policy changes:

Reform the Community Input System

Neighborhood feedback needs to be more representative of the community, rather than a vocal minority. Groma is planning to build a voting platform called “Polis” that could help democratize input during the development process. Polis is a blockchain-based system of soliciting and recording votes on development proposals that reach a certain stage of planning. We hope to create seven voting Strata regions, ranging from immediate neighbors of the proposed development to all residents within a given country. How officials use and/or weigh the voting data from the different Strata will be up to them, but the goal is to have more voices heard so that the process is representative of the community.

In addition, neighborhood input must be reconsidered to be only one of multiple competing interests when approving housing. For example, it should be weighed against the community’s housing needs and the actual merits of the projects. We are cautiously optimistic about Mayor Wu’s proposal to update Boston’s zoning code, as she has promised to reduce the power of neighborhood groups in the process. The devil is, of course, in the details, but we’re encouraged by this direction.

Eliminate Single-Family Zoning Statewide

Massachusetts should pass legislation to ban single-family only zoning, so that apartments and multifamily homes are legal throughout the state again. This isn’t an unprecedented action - Oregon eliminated all single-family zoning in 2019. In addition, municipalities should reform their zoning codes to make multifamily developments by-right, and we support reducing or eliminating minimum lot sizes.

Upzone and Increase By-Right Zoning

Boston’s zoning code should be rewritten to match the current, physical realities of the city, so that there are no more “nonconforming” buildings. We support upzoning residential areas in Boston, especially near transit, to encourage new housing. That upzoning should be done by right, with city officials and the public working together to write a priori criteria for developers to meet. The code should maximize the amount of by-right development with clear zoning requirements and minimize the need for zoning variances wherever possible.

We support Abundant Housing Massachusetts’s proposal to permit housing up to five stories or 60 feet by right throughout Boston. We also advocate for a “double height by right” policy in the city, which would allow developers to double the height of existing homes by right, either by adding new stories or building new homes on purchased properties. Even with the adoption of these policies, individuals would still be able to provide input during the development process, notably as it concerns architectural style and the size of proposals larger than what would be permitted by right. We believe this would comfortably reconcile people’s interest in maintaining neighborhood character with the need to build more housing.

Conclusion

It’s understandable that people feel strongly about local input and retaining leverage over new development. However, we have to balance opposition to change with addressing the Boston area’s current needs. Greater Boston is facing a housing crisis, and we must change our policies to respond by building more housing.

Consider the origin of Boston’s 15,000 triple-deckers, which are now an iconic part of the city. Triple-deckers were mostly built between 1870 and 1910 to accommodate large families moving to the city to take advantage of a manufacturing boom. In other words, these homes were built to meet the exigencies of their era. In the past 150 years, much has changed in Boston, not least its economy and demographics. Boston adapted to meet its population’s needs then, and we must do the same today.

A renter is “cost-burdened” when they spend over 30% of their income on housing.

A tragicomic example: the Cambridge Planning Board once fought with a pizza shop in Harvard Square over whether the color of its umbrellas should be black or “white with black and pink dots”.

The floor-to-area ratio describes the proportion of square footage in a building to the square footage of the lot of land.